Most organization design efforts begin too late.

Not too late in the change process, but too late in the thinking. By the time new boxes are drawn and alignment initiatives launched, the most valuable design data, the informal patterns, tensions, and workarounds already shaping behavior, have gone unexamined.

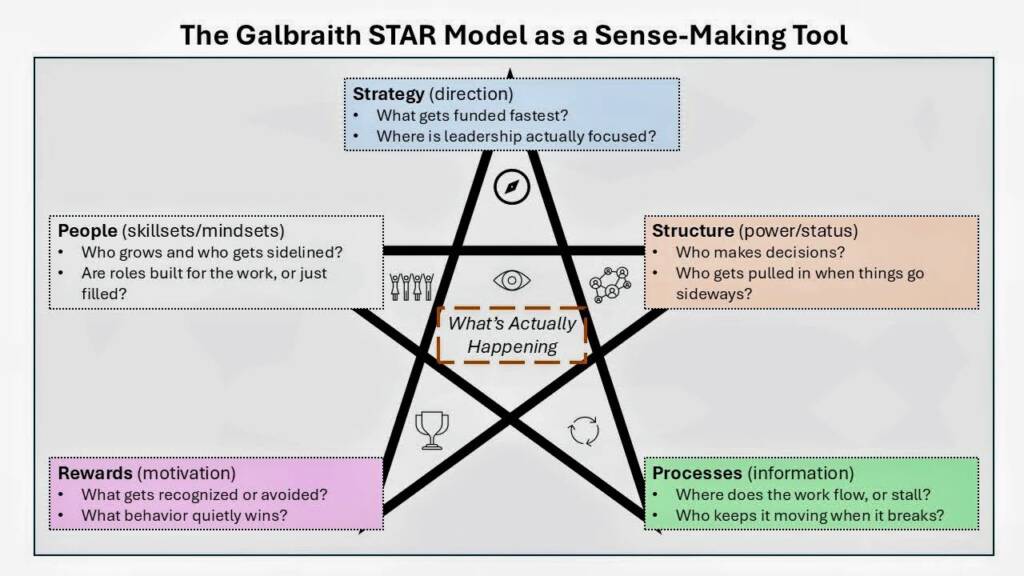

This is why I use the Galbraith STAR Model, not as a planning framework but as a sense-making tool. Not to impose a theoretical structure on an organization but to surface what’s already governing how people work, decide, coordinate, and adapt.

Originally developed by Jay Galbraith (2002), the STAR Model outlines five interdependent elements of organization design:

Strategy, Structure, Processes, Rewards, and People.

These were intended as levers to shape behavior in support of strategy. In today’s dynamic, complex environments, it is less about how well these are aligned on paper and more about how they interact in practice.

In this context, design is not a blueprint; it is an evolving, participatory capability that must start with what’s already happening.

Organizations Are Adaptive, Not Engineered

Organizations are not machines. They are social, adaptive systems held together as much by informal influence and interpersonal trust as by formal structure.

People do not wait for the org chart to make sense before acting.

They compensate. They invent workarounds. They stretch roles to fill voids and create micro-structures that support the work.

This isn’t dysfunction; it’s emergence.

And using the STAR Model as a sense-making framework reveals these invisible threads.

I’ve described this before as the tangle of complexity:

- Roles are shaped more by relationships than by descriptions.

- Processes evolve in tension with constraints.

- Influence, decision-making, and trust flow through informal channels.

Good design doesn’t eliminate this tangle; it engages with it, learns from it, and shifts it carefully.

Each STAR Point as a Sense-Making Prompt

Rather than asking, “What should we design?” I ask, “What is already designed through action, not intention?”

Each STAR point becomes a domain of inquiry and intervention.

1. Strategy: What gets protected when resources are tight?

Strategy is often most visible when constraints emerge. It’s less about what’s stated and more about what gets resourced, defended, or quietly deprioritized.

Practitioner prompts:

- What gets done without approval?

- What projects always find budget?

More like -> noticing where energy and resources are pulled in practice

Less like -> assuming strategic alignment because the mission is printed on mugs or t-shirts

2. Structure: Who holds real authority and decision rights?

Structure is not a diagram. It is the lived reality of who people go to, who they trust, and how decisions move.

Practitioner prompts:

- Who mediates when there’s conflict?

- Where do decisions get stuck?

More like -> mapping informal influence and authority

Less like -> adjusting boxes and hoping behavior follows

3. Processes: Where does the work flow, and where does it stall?

Processes are usually created by necessity, not intention. If the formal process fails, people still get things done; they just do it informally.

Practitioner prompts:

- Where do people say, “We just figured it out”?

- Who makes the process work despite the system?

More like -> co-mapping how work actually moves across teams

Less like -> writing new SOPs that nobody reads

4. Rewards: What behaviors get repeated or avoided?

Formal rewards matter, but informal signals matter more. Behavior is shaped by what people see being celebrated, avoided, or quietly punished.

Practitioner prompts:

- Who gets recognition, and for what?

- What risks are people unwilling to take?

More like -> surfacing the unspoken reward system

Less like -> assuming comp plans shape all motivation

5. People: Who is carrying extra weight, and who is underutilized?

People often adjust to fill the design’s blind spots. The system may formally ignore a problem, but someone is informally solving it.

Practitioner prompts:

- Who’s always stepping in to hold things together?

- Who isn’t being stretched because the role is too small?

More like -> designing roles around evolving work

Less like -> slotting people into outdated job descriptions

Example: The Cross-Functional Friction You’ve Probably Lived Through

A leadership team at a regional healthcare network sought help with structural redesign. They assumed their problem was coordination; projects moved slowly, timelines slipped, teams pointed fingers.

But structure wasn’t the real issue.

Using the STAR Model as a sense-making tool, we uncovered this:

- Strategy: “Patient-centered care” was stated, but departments were rewarded for throughput and efficiency metrics.

- Structure: Dual-reporting lines created confusion and delayed decisions.

- Processes: Teams built manual systems to bridge gaps in scheduling software.

- Rewards: Risk-takers were seen as troublemakers. Those who avoided conflict were promoted.

- People: Senior nurses informally took on logistics, scheduling, and HR on top of clinical duties.

The solution wasn’t a new organizational chart. It was to make the informal visible and then redesign incrementally from what was already working.

Small shifts followed: clearer decision rights, revised workflows that integrated existing informal tools, and resource reallocation to relieve hidden labor burdens.

Trust improved. Cycle times dropped. The design emerged with the team, not around them.

Design as Capability, Not Deliverable

When the STAR Model is used for sense-making, it fosters shared ownership and insight across the organization.

It allows leaders and practitioners to shift from fixing to framing.

From prediction to participation.

From abstract alignment to concrete emergence.

More like → uncovering how the organization survives itself

Less like → creating the perfect design in isolation

Design becomes a capability. Practiced in conversation, in iteration, and in context.

Reference

Galbraith, J. R. (2002). Designing dynamic organizations: A hands-on guide for leaders at all levels. Jossey-Bass.