This is an edited repost of an idea I shared earlier.

There is a false belief that the actions and behaviors we see in the present have always happened and that they must continue. This brings us into a problem-focus. While problems are essential and must be acknowledged, the more effective focus is determining the solution – what we want to happen. This happens through a solution-focused process of looking for exceptions and finding already existing small steps to take.

What?

It has happened to all of us. Someone at work (your manager, coworker, subordinate, peer, vendor, customer, etc.) pisses you off, and you go off on an angry tirade about “What a jerk they are – they always do this. I cannot stand working with that person.” Or, “The engineers are always so smug and condescending to us; don’t they understand the pressure we are under!?” Or, “Every time I lead a meeting with the financial team, they just sit there and stare at me; they never offer anything useful.”

On and on and on…

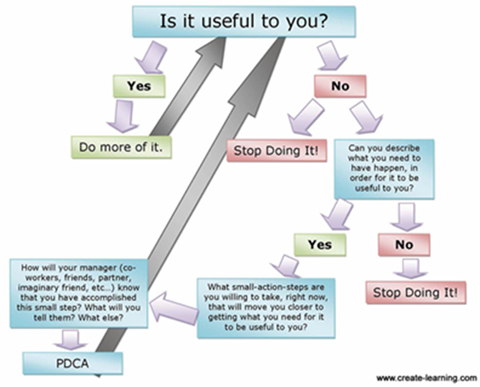

While these statements may be factual, they are neither useful in creating solutions nor getting the work done.

When coaching teams and individuals, many complaints come to the surface. These complaints often construct the reality of how the team operates and how the team members treat and act towards each other.

There is an exception

Rather than focus on the problem, focus on the solution by developing a folkloric construct reinforced by the team’s shared language, actions, and stories about the “others.”

“…all meanings, since they are the creation of unique persons in unique settings, are distinctive. Furthermore, since our knowledge of the world is inescapably subjective, human interaction is about a transformed and imaged world. It is not the “real” world, but these transforms that we fight about, laugh about, cry about. Our meanings are fictions, valued and useful fictions, but fictions nonetheless.” –Barnlund 1981

These fictions can be seen as cooperation or resistance; they are one or the other.

As you and your team create these stories of how challenging it is to work with the “other,” the words, actions, and views about them develop into deep patterns of resistance.

So What?

Reinforcing resistance patterns only dig you deeper into frustration.

When people are working with teams, they want the challenges to stop; they want their manager to “Stop being so micromanaging,” they want their subordinates to “Stop coming to them with every little problem,” and they want their team to “Stop fighting amongst themselves.”

All this does is a resistance point and reinforce the teams’ view of the resistor.

The breakthrough hinges on determining what you and the team will be doing when “Your manager stops micromanaging,” “Subordinates stop coming to you with problems,” or “Your team stops fighting amongst themselves.”

We can only measure progress on results.

Now What?

If the challenges you and your team are having stop tomorrow, how can you know that they will not start back up the following day, week, or month?

“Simplicity does not often come about spontaneously. Rather it evolves over a period of time and through a process that involves a lot of complicated thinking.” –Steve de Shazer

Instead of looking for the problems’ resistance, I suggest you start looking for the exceptions’ cooperation.

“I have come to realize the practical clinical importance of the folkloric idea that all ‘rules include exceptions’. We have come to define exceptions as ‘whatever is happening when the complaint is not’.” (de Shazer 1985)

No matter how small, there is a time when the complaint does not happen.

You need to find and examine that time and patterns, language, behavior, actions, environment, conversations, etc.

By finding a time when things went the way you needed them to go, the absence of your problem becomes your solution; you and your team can develop patterns to reproduce that.

For example, suppose your team keeps fighting amongst themselves; thus, the project is late, over budget, and of poor quality. Working with many teams with the above complaint, we have been able to find the exceptions of when the team ‘Got along, everyone trusted each other, and the work got done on time, within budget and quality specifications.’

So the energy now changes to asking the team to describe what happens in detail (concrete, tangible language) and when they get along and accomplish their work. This shifts the assumptions from resistance to cooperation and reframes the team and the folkloric construct to one of ‘getting along’; finds cooperative patterns.

While our primary focus is on the pattern of the solution and leads to what the team needs to do to improve in a collaborative effort continually, our secondary focus is on exploring the differences between getting along and not getting along. Through this secondary process, we can find even more exceptions to increase the pattern of getting along.

Once we know that the team can get along because they have described the exception with concrete, tangible words, the problem can be solved much more quickly. The team can be encouraged to use the getting along patterns even if they realize and feel they are not getting along.

What do you think?

What patterns can you compare between the resistant and cooperative actions you see? Can you find the exception or what happens when the problem is not happening? How can you use the above ideas, models, and patterns to improve your work?